Livestock Guardian Dogs at Work Another Side of The Great Pyrenees Mountain Dog

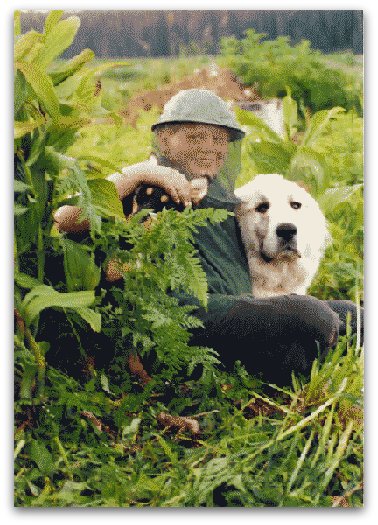

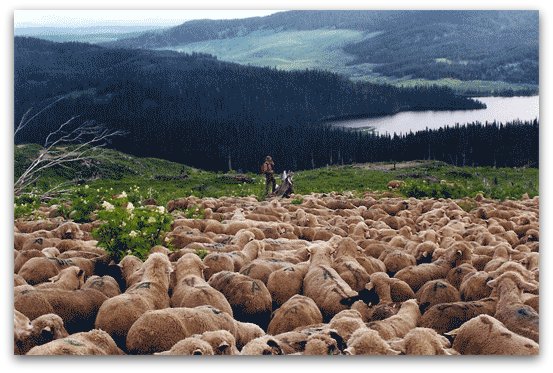

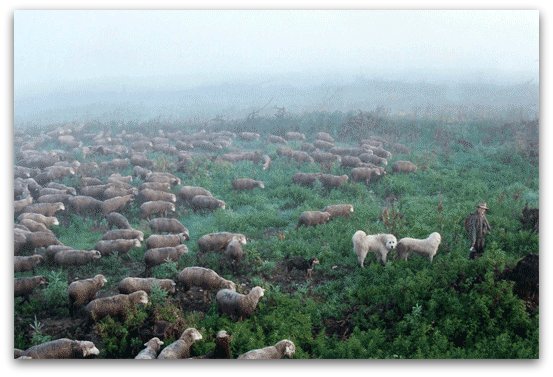

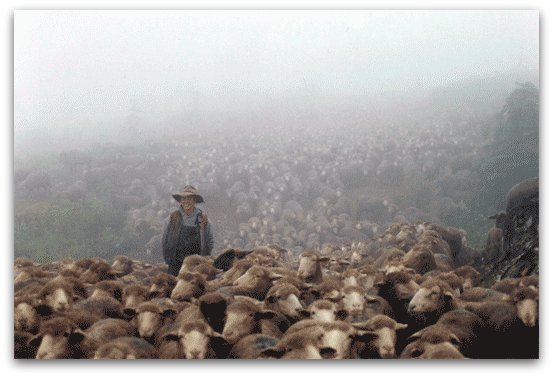

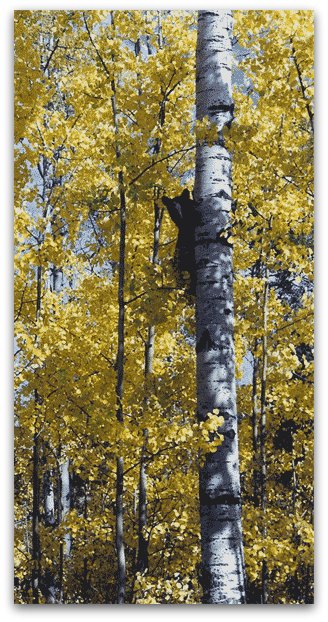

Here are real life accounts of the Great Pyrenees used as Livestock Guardian Dogs in the protection of reforestation workers and shepherds in the interior of British Columbia.

As pets and show dogs, we know the Great Pyr well. And some of us have seen the Pyr in action as livestock guardian dogs on the farm or have seen the guarding instinct as it protects the home and family. But this article shows the Great Pyr at work in the rugged country of British Columbia. You will be amazed at just how much protection there is in a Great Pyr!

The Club thanks Mr. Dennis Loxton, the Western Silvicultural Contractors' Association and BC Forest Safety Council for granting express permission to reproduce the following article for the benefit of visitors to our site.

At the end of this page look for the link to an amazing story of a family pet that protected its family from a Bear attack.

Bear Dogs: A Silvicultural Tool by Dennis Loxton.

Bears—and the possibility of being eaten by one—are a very real part of normal life for BC silvicultural workers today. It does not have to be so. I firmly believe that dogs, and particularly livestock guardian dogs, can reduce bear attacks on BC silvicultural workers. (By the way, I’m not trying to sell you a dog.) I believe that nobody should be asked to work in silviculture in the forests of BC without a guard dog, and that livestock guardian dogs should be accepted as a standard silvicultural tool on all BC reforestation projects.

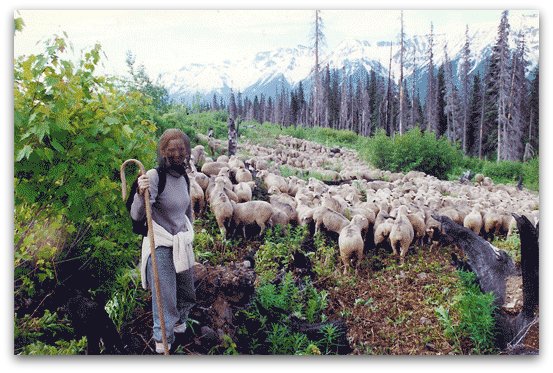

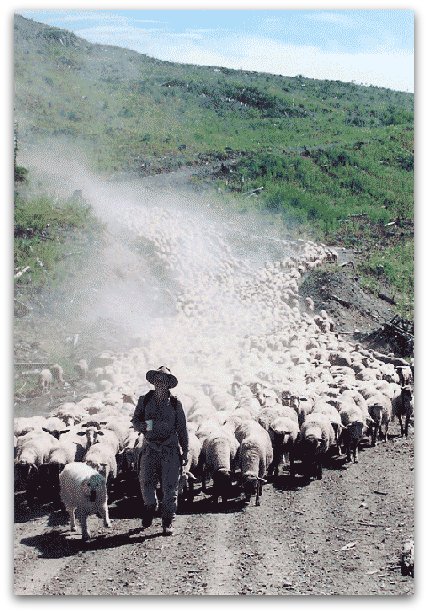

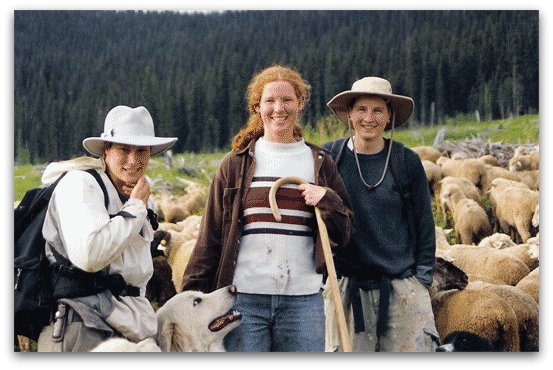

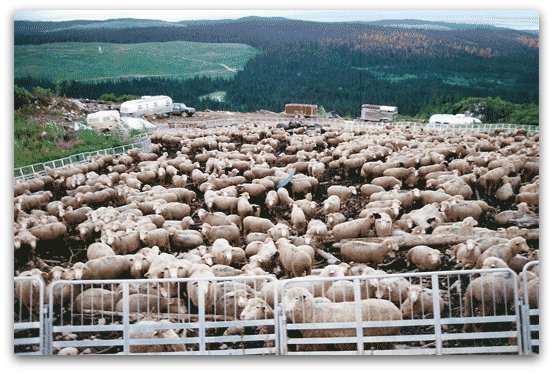

I have been a silvicultural contractor for 34 years (17 years tree planting contracting, employing 100 to 200 planters per year, and 17 years as a sheep vegetation management (sheep veg. mgmt.) contractor using approximately 6,000 sheep per year. We have always worked way out in the boonies and we have taken more sheep further out bush than anybody in Canadian history. Lots of our sheep veg. mgmt. work was in the Stewart area of BC, which is famous for its high grizzly and black bear populations.

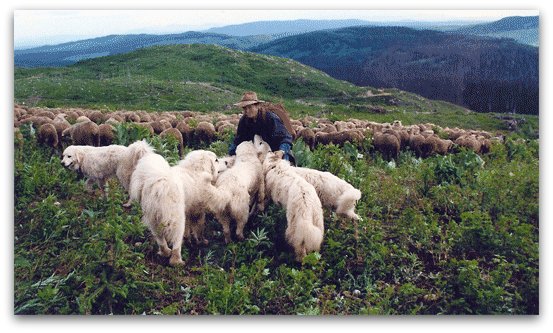

We were laughed at and told we were nuts when we first proposed to take 6,000 sheep to plantations 100 km out bush from Stewart on the west coast, but we were confident that good BC shepherds and 50 dogs would keep the sheep safe. We pride ourselves in being good shepherds and we try not to harm or kill any animals, including predators, for any reason. The fact that we have only lost a total of eight sheep to bears and wolves in our 17-year sheep veg. mgmt. contracting experience speaks for itself. We believe that our sheep are safer from predation when they are out bush with us and guarded by livestock guardian dogs than they would be at home in most Canadian sheep farmers’ fields. The neighbor’s dog would probably kill far more than eight sheep over a 17-year period.

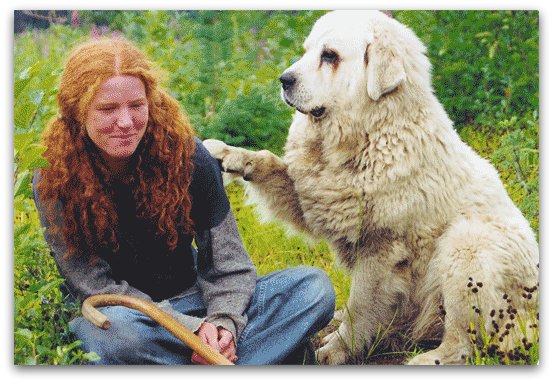

I have used dogs to guard silvicultural workers and sheep from bear attacks for about 30 years, and I personally never go into the forest without at least one dog. Most dogs will guard you against bears, but livestock guardian dogs will guard you better. Just as Greyhounds were bred to run and Labradors were bred to retrieve ducks, livestock guardian dogs were bred to guard. Now it’s simply a matter of choosing the best tool for the job.

Livestock guardian dogs have evolved over about 5,000 years of selective breeding and ruthless culling. People ate dog for most of that time and it is only recently that man could afford to feed large, non-productive, pet dogs. Guardian dogs that ran away from attacking bears or wolves usually ended up as supper for the farmer. They certainly were not fed or used for breeding. The end result of this 5,000-year breeding program is that today’s guardian dogs have had fear bred right out of them. They will guard your family, livestock, chickens, or silvicultural workers against anything, fearlessly, until they die.

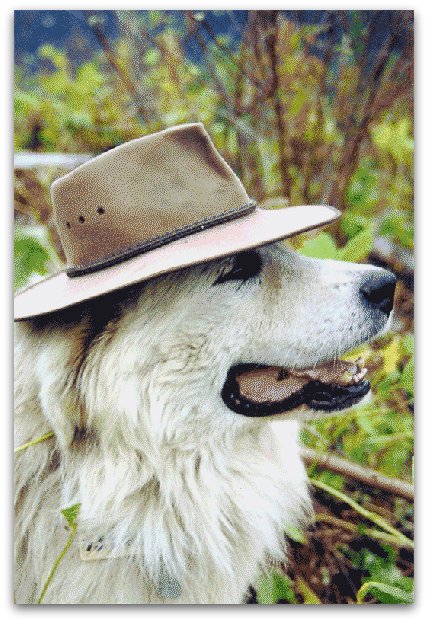

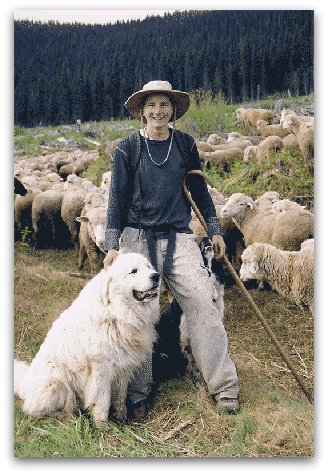

The word “fearless,” in the case of our faithful Great Pyrenees dog “Tiger,” means a 150-pound dog squaring off with a very determined 1,000-pound grizzly bear and not backing down at all.

The previous year, some tourists had stolen Tiger and taken him over the border into Alaska. He stopped eating, got sick and very skinny. Eventually they took him to an animal shelter, where the staff decided to give him a haircut. Tiger put a stop to that about half way through the shearing process. The RCMP located him for us and we got him back via the mail plane, $1,400 later. He was a mess. Then, one of his pack mates mouthed off about his bad hair cut and a major dog fight exploded. Tiger took a pounding and was in really bad shape, so off to the vet we rushed. He barely pulled through, but by the next summer he was his normal happy, tough self and back at work.

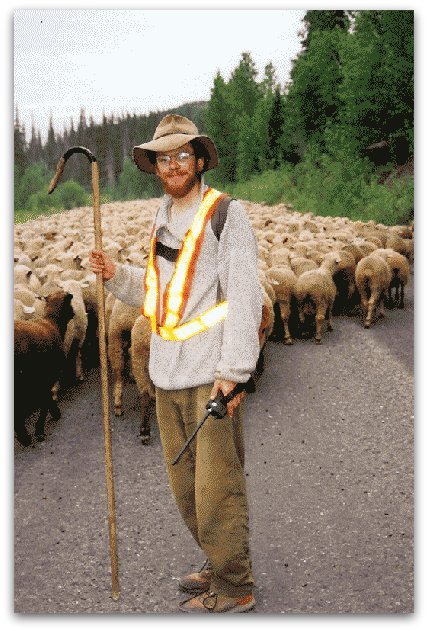

The shepherds were trailing the 1,500 sheep flock down a logging road, through the dense forest to another block. Suddenly, right at the perfect place for an ambush (a switch back with a steep drop off on one side), a large, predatory grizzly charged into the rear of the flock—determined to get a sheep. Two of the dogs were able to hold back the snarling grizzly, lunging and ducking the bear’s swatting claws, until the other guardian dogs arrived. My son Daniel was only a few meters away and had a better view of the fight than he would have preferred. He scrambled back into the centre of the flock, which is the safest place for a shepherd in a bear attack situation. (The theory being, “If the bear really wants something to eat, better a sheep than us.”)

The bear retreated, disappearing into the forest with the dogs at his heels. The shepherds took this opportunity to get the flock briskly moving again. Soon, Daniel was jogging along after the sheep—making him the last animal in line.

Turning to look behind him, Daniel stopped dead. The grizzly was right there, sprinting straight at him, almost on top of him.

“You think you’ll react in a situation like that,” Daniel recalled, “but it happened so fast. I just blinked, stood there and waited to die.”

Suddenly Tiger was there, blasting past Daniel, 150 pounds of teeth and viciousness. The dog’s attack deflected the bear’s charge off to the side of the road, and almost certainly saved my son’s life. Within seconds the other guardian dogs arrived to help Tiger. A major battle exploded right behind Daniel as he pushed his way into the safety of the flock.

The dogs were able to drive the bear back into the forest and the dog pack took up their defensive positions all around the flock again. Minutes later, the flock reached the open block. No sooner had they arrived than the bear attacked yet again, charging straight up the road towards where shepherd girl Lesley was frozen in fear. The crew yelled at her to jump into the middle of the flock, but she could not move. Suddenly there was Tiger again, fighting like crazy, and once again, he held the grizzly off until the other dogs arrived. Another huge battle erupted and the dogs chased the bear back into the forest again. Lesley jumped into the safety of the flock. The dog pack returned to their defensive positions, evenly distributed around the flock, all extremely serious and definitely on guard again.

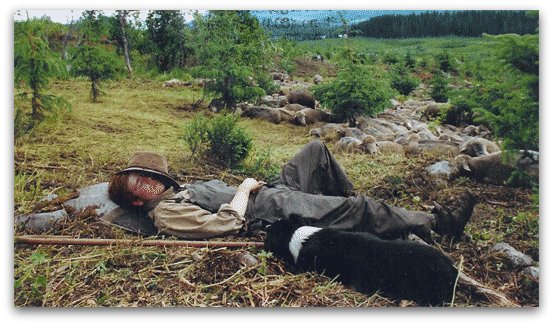

We set up a temporary camp. The dogs worked all night, full alert, deadly serious, fearless guardians doing their job. The bear left during the night and next morning we all just went back to our sheep veg. mgmt work.

Later, a movie crew filmed a documentary for the television program Dogs With Jobs featuring “Tiger: Bear Dog,” which showed in 63 countries. Tiger did actually tree a black bear for the film crew, but he was only playing and wagging his tail the whole time.

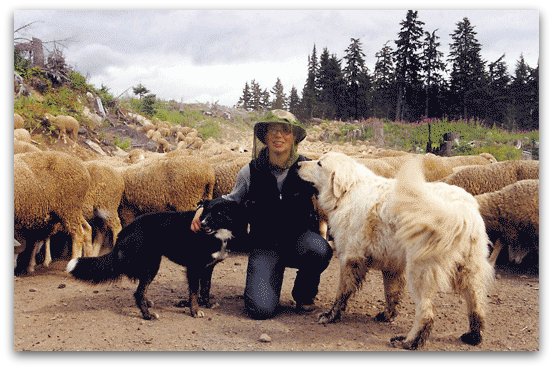

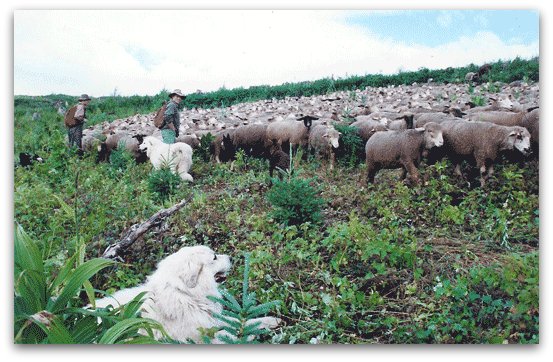

The early sheep farmers of Canada and the USA imported the finest European guardian dogs, so Canada already has excellent guardian dogs. I usually purchase mine for $400 to $600 per pup, and since they can work for about 8 or 9 years, I see them as one of the great bargains of today. They work well as individuals, but better in pairs. They use excellent team work with complicated strategies that continue to amaze even my most experienced shepherds. For example, if a young yearling black bear comes onto a plantation, the experienced older dogs will instruct the younger dogs to run up and chase it away, but if a large grizzly comes, they clearly instruct the younger dogs to stay with the flock while the biggest and toughest dogs attack the bear.

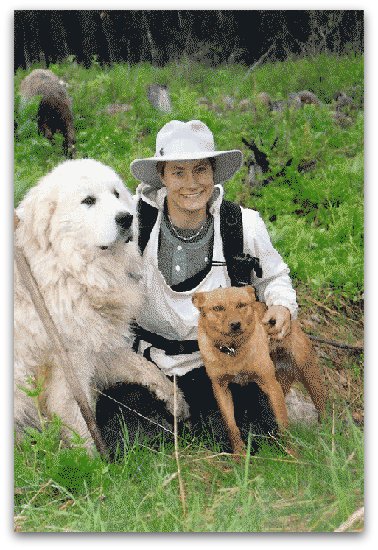

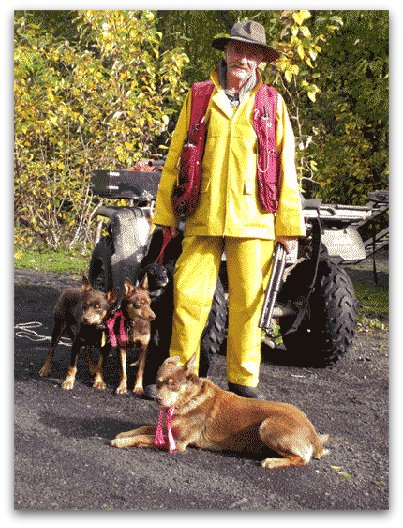

We used to think that a pack of three guardian dogs was ample for bears. Then we went further north and saw the size of the northern grizzlies, and encountered packs of 12 wolves. We learned to increase the guardian dog packs to eight dogs per 1,500 sheep flock. It also needs mentioning that the shepherds have four Australian Kelpie sheep herding dogs per flock. The Kelpie breed is half dingo and very hardy. They love chasing bears. When a bear comes and the guardian dogs take off after it, the herding dogs get involved too, so the bear is confronted by a dog pack of about a dozen barking, snarling dogs. (Definitely a serious deterrent for even the most hungry grizzly!)

In the case of silvicultural workers, I think that one livestock guardian dog per plantation would do the job, but a pair would be much better. Since bears are opportunists looking for an easy meal, when they encounter the dogs, it usually doesn’t take them long to decide that they are better off eating berries and fish or something that represents less hassle. It is all about the “hassle factor.”

The dogs rarely actually bite a bear, but they put on such a show of viciousness that they clearly represent a huge hassle to that bear. It will usually leave as quickly as it can. (Don’t think the dogs are afraid to bite the bear, but rather that this is their strategy: be as intimidating and as big a hassle as possible, and chase the bear away without harming it.) Although the guardian dogs seem quite gentle and laid back, they are also large, very powerful, quick and vicious animals. However, they never show that side of their character unless the situation requires that response.

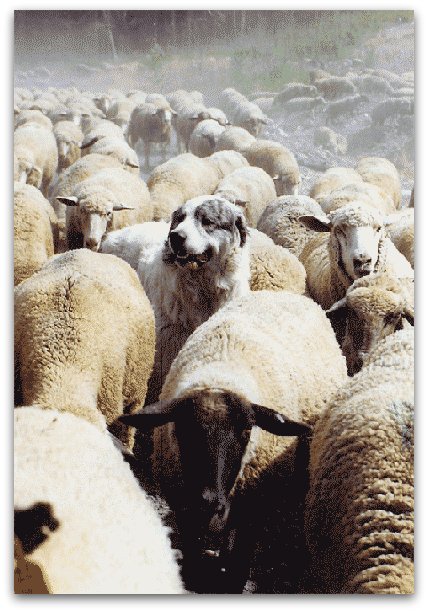

Most guardian dog owners have no idea how much dog they have. They will tell you that “they own a Great Pyrenees, but he’s not really much of a guard dog and in fact he’s a big, friendly, tail wagging goof.

He loves to hang out with the wife and kids. All of the neighbor’s kids love him, babies hang on his tail and ride him, but he wouldn’t harm a fly. We all like him so we keep him.” I hear that story often and then I try to explain that their dog has never had reason to show his tough side, so they have never seen that side of him, but should someone or something threaten to harm the family, that dog would instantly transform into one powerful, ferocious animal that will never back off. It will not stop until the danger is past and that the speed and viciousness of the response will absolutely shock them. Of course they don’t get it. Fair enough—how could they? How could they ever grasp that “Fluffy” the gentle giant is really the equivalent of a lion in a dog’s body? I have witnessed that transformation dozens of times and it really is always a shock to experience.

One example I witnessed was a dog fight between two mature male Great Pyrenees guardian dogs and a large mature male Hungarian Kuvasz. The fight exploded right in front of another shepherd and myself. It was a territorial dispute, and the Pyrenees were brothers who had decided to kill the Kuvasz. We were able to get our shepherds crooks hooked onto the collars of the two Pyrenees, and we pulled them off of the Kuvasz. The whole fight lasted seconds, but already my Kuvasz was clearly dying. He weighed about 150 pounds and was one of our best dogs, so we quickly made a “bush stretcher” out of two long sticks and our sweatshirts and carried him to the truck. We rushed him to the vet 100 km away. He was almost dead on arrival but we told the vet to hit him with everything that he had and try his best to save him.

The vet examined him, then asked, “Did the driver of the truck stop after running over him?” We explained that it was a dog fight that only lasted seconds and that we were right there and had witnessed the whole thing. The vet refused to believe us. He pointed out the numerous broken bones, major internal damage, the rips and deep gashes all over etc and to this day I think that he still believes that a truck ran over my dog.

Of course the dog died. The crazy part of it all is that I have seen those same two Great Pyrenees lick and comfort a sick lamb all day and then be clearly quite distressed when they could not save its life.

The five most popular livestock guardian dog breeds available in Canada are France’s Great Pyranee, the Hungarian Kuvasz, the Italian Maremma, the Turkish Akbash, and the Komondor.

They are all excellent, but I feel that some of these breeds are much more suitable for the job of guarding silvicultural workers than others.

I really like and so recommend the Great Pyrenees for the job. They always seem happy and friendly, but underneath all of that tail wagging and smiling is a big, serious dog. When he “kicks into gear and goes to work,” he definitely means business. They are a large breed usually weighing about 150 pounds, but sometimes getting up to 200 lbs body weight. The Pyrenees is more of a “big bruiser,” than an athlete, with a deep, powerful voice. He is a low metabolism animal and so he eats about the same amount of food as an average sized dog. He is very hardy animal and completely happy sleeping out in the snow in mid winter. He doesn’t seem to need much of anything. I have seen some Pyrenees guarding sheep flocks on the prairies, while living completely “off the land”, catching and eating gofers, mice and rabbits. They were in good condition and doing just fine.

The Kuvasz is also a very impressive dog, but more of an athlete, burning up more energy and so eating more food. He is a powerful, fast runner and he charges the bear immediately upon detecting it. A dog pack combining both Great Pyrenees and Kuvasz works wonderfully, but the Kuvasz loves to patrol a very large area and so is harder to keep at home during the off season.

The Italian Maremma is also an excellent dog, similar in nature to the Pyrenees, powerful and effective. I think that they are marvelous workers and my shepherds definitely like them on their work site. Project manager Jolene Shepherd prefers a dog pack combining Great Pyrenees, Kuvasz and Maremma, with each breed bringing their particular strong points to the pack. Her projects have never had a sheep killed by a predator, so it makes sense to me.

The Komondor is also a large and very serious guardian dog breed. He has been bred to grow long dreadlocks that reach the ground. When he comes running at you he looks strange and very scary. The idea of the dreadlocks is that they mat together, get sticks etc. caught up in then and form a type of natural fang proof armor. This is very effective protection when fighting a wolf pack. Most owners shear them annually. Shearing dogs is a chore that I’d rather not bother with, so I don’t have much experience with the Komondor breed.

The Turkish Akbash is an extremely serious dog, but very aggressive and I don’t like them. One Akbash owner tried to justify the breed’s temperament by explaining “whereas other guardian dog breeds were bred to guard against predators, the Akbash was bred to guard against predators and bandits.” Great! I think that it is beyond the capability of any dog to sort out the bandits from the legitimate clients in the BC forest industry. Clearly somebody will get bitten by a big angry dog. Because of this issue, I definitely do not recommend the use of Akbash to guard BC silvicultual workers.

When training livestock guardian dogs to guard your workers against bear attack, it really is not as complicated as most people would think. Firstly, guardian dogs want to guard you, they can’t help it, that’s their strongest instinct. Its better if there is an older, experienced dog to teach them the ropes (for example, to chase the bears off of the block that you are working on, but not to bother going off into the forest looking for grizzlies to chase). Bonding them to the crew is easy enough. They should simply feed them, pat them, befriend them and the dogs will want to hang out with the crew and guard them 24/7.

When the crew arrives on the block, the first job is to release the dogs. They will immediately and happily go to work. They will run around the block and chase away any animal that they encounter. This does not take long, usually about the same amount of time that a crew takes to get their gear together before they start work. The dogs will continue patrolling the work site all day, and they really love their job. At the end of the day they will jump up into the back of the pickup truck and go home with the crew. If you are in a camp situation, they will patrol and guard the camp all night. I believe that the added safety that guardian dogs bring to the work site increases crew productivity, which helps to offset some of the costs of purchasing and maintaining the dogs.

You don’t really have to bother teaching them much, the guarding comes naturally, but some things that seem really obvious, I had to learn the hard way. To begin with, don’t forget to teach them to (1) come when they are called, (2) jump up into the truck on command and (3) lead. As silly as this may sound, we have had dogs that nobody bothered to teach to get into the truck or to lead. This happened easily enough. We had 50 working dogs at the time

Then, later in the season, three dogs tried to get a porcupine to leave the block. They got too close and got a few quills each. Then they got vexed and regardless of the pain, tore that porcupine to bits. With about 300 quills in the mouth, nose and throat of each dog, we had to take them all to the vet—but they would not jump up into the truck. It took two people to load them, which meant two lost man-days as both shepherds had to go to town and physically carry three 150-pound dogs into and out of the vet clinic. Everybody felt foolish. Most of all, the contractor (me) felt particularly foolish, since the total bill for the event (wages, vet, truck etc) was over $1,000. Well, that’s contracting. Picking up the odd unexpected bill seems to be part of it all.

As a point of interest, and because it often comes up in conversations about guardian dogs, the old-as-time technique used by shepherds for bonding dogs to sheep flocks is to take a puppy from its litter just as a ewe is about to have twin lambs, then when the first lamb is born, they get her afterbirth and rub it all over the puppy. When the second lamb is born, they put the puppy beside the newborn lamb when the ewe is not looking and (usually) she can be tricked into thinking that she gave birth to the puppy. The ewe will lick it clean and care for it. The puppy accepts that the lambs are his new litter mates and grows up with them. That dog will guard those lambs and ewe, plus all of their friends and relatives, which of course is the whole flock, for the rest of his life.

Regarding the feeding of guardian dogs, commercial dog food is the simplest, but in a camp situation, camp scraps are usually ample. If buying dog food, better formulations from middle-of-the-road brands are good enough. I think that the most prestigious brands and top-of-the-line formulas are overrated and too expensive, while the cheaper stuff (as with all low bids) is usually low on product and high on filler—leaving you with more dog turds for somebody to clean up later.

We feed our dogs once per day and always before we eat our supper. “Free feeding” works well in the off season, but not during the work season, because the dog will often be preoccupied with guarding his food bowl against his fellow pack members. It’s best to avoid that kind of distraction from his job. Working dogs need to be wormed twice a year and we find that spring and fall treatments work best. They also need to be vaccinated annually.

My first experience with bears, tree planting, and wishing that I had a dog with me, all happened on the same day, about 34 years ago. It was in the very early days of BC tree planting contracting that three friends and myself took a “fly in” tree planting contract. The helicopter dropped our trees, gear and us off and the pilot said that he would be back in a month. We were on the other side of a river and mountains and pretty well nowhere. It was a very “lean show” without radio, First Aid supplies, firefighting equipment or much of anything. We did, however, have a mail order .303 rifle ($30 incl. S and H) in case bears came. Our previous bear experience was limited to koala bears. Basically we didn’t have a clue.

We limped home to camp at dusk after our first day of planting to see three bears leaving our trashed camp. They had eaten about half of our food and we were on strict rations thereafter. The bears hung around every day and night, despite the huge slash fire that we kept burning. We had plenty of slash, but it did not work, as the fire did not bother the bears after a while. We probably kept the fire going because it made us feel better. Warning shots did not work either. I wished that I had my dog with me, but he was in Australia. Then it started to rain and our cheap boots and raingear fell apart. Things were getting fairly rough at that point, but we were young and making good money, so we continued working from daylight to dark, seven days a week, until we had planted all of the trees. Needless to say, we were fairly feral by the time the helicopter came. I decided to become a tree planting contractor after that, but vowed to get much more serious about bears, bear dogs, boots, rain gear, equipment and contracting in general.

We soon had the best equipped, best fed tree planters with the best camps, boots and raingear in the industry, and all of our camps had a camp bear dog. The BC tree planting industry quickly became the world leader in high quality, high production reforestation, employing thousands of young Canadians. It was fun to enjoy the status of being amongst the top few tree planting contractors in BC, and so, one of the top tree planting contractors in the world.

However, things were still not perfect regarding bears. The camp cooks demanded that the bear dog stay in camp, and so the planters themselves were still exposed to potential bear attack. Girls were chased off of the block three times over a two-day period. They said the young black bear was “only playing.” Other planters did not see it as fun and would not get out of the truck. I took the camp dog to the block for a few days to deal with it. Meanwhile another black bear had come to camp, trashed some tree planters’ tents and finally was shot by the foreman as it sat eating granola, right in the middle of the cook tent. The cooks were angry with me for taking the dog to the block, and demanded “their” dog back. When I brought the dog back to camp, another bear showed up on the block and scared another planter. I lost patience with the whole situation and shot that bear.

Things got crazy at that point as I had completely misjudged how many animal rights activists I had employed. A large potion of the crew threatened to quit in protest over the shooting of the second bear, as he was only about half grown and had looked quite cute. The obvious lesson I learned was that I needed more dogs, one for camp and others for the work sites.

I saw some (rookie) tree planters walk up too close to a large black bear to “get a better photo.” Bear information and bear avoidance lectures became a standard part of our tree planter training program from then on.

The speech went something like this: “Bears live here and bears eat people. They don’t prefer to eat people, its just that they eat pretty well anything including vegetation, berries, fish, carrion, apple pies, garbage, toothpaste, grubs, insects, people, deer, moose, cows, sheep, bears, candy, etc. They don’t hate you or like you. They don’t care. You are just protein to them. Just like a shark or crocodile, they find food and they eat it. Bears hunt by stealth and ambush. They are very fast (much faster than you), very strong (they can kill a moose), silent, and invisible (they can sneak up and catch a deer, which is all ears and eyes). They can climb trees, and they are searching for food every waking minute. But they are opportunists, always looking for an easy meal (like the candy and cookies hidden in your tent). Many of them are already spoiled by easy food from sloppy campers, fishermen, and garbage dumps, and some are even problem town bears relocated to your work site by your Government. But you are smarter than bears, so use your brain! Don’t keep food in your tent, don’t go up to them for a better photo, and do trust your “sixth sense”: if you feel like you are in danger, you probably are. So leave. Most of all, don’t represent easy protein.”

In the case of shepherds we add, “and if a bear comes, go to the centre of the flock, keep as many sheep as you can between him and you, then let the dogs deal with it.” Most silvicultural workers already know all of this, but a surprising number of them don’t. I feel that the speech is always worthwhile anyway.

Last year I had a reminder of how little some silvicultural workers know about bears. Four of us were doing regeneration surveys. I was at the far end of the block with my personal dog. A colleague named Ben was at the opposite end. When he neared the tree line, he was charged by a large black bear. She had very young, twin cubs. He dropped his new stainless steel shovel, jumped over a small cliff and ran back to the truck, yelling into his radio the whole time. At the truck they decided that since we had finished the job, except for the two plots Ben had left to do, we should all go back to Ben’s section together (safety in numbers theory) retrieve Ben’s shovel, do the two plots, then go home. They were quite surprised when I said “I’m not going and what’s more, one of you is going to die.” The fact that the bear had newborn cubs and would not care if there were 100 of us, had not entered the minds of these three fairly bush-savvy country boys. About one month later, two of us went back with five dogs, finished the job, got Ben’s shovel and all was fine. Ben was so traumatized by that bear experience that he quit the silviculture industry and got a job as a fashion model in Indonesia. The BC silviculture industry lost another good man to bears.

On one of our sheep veg. mgmt. contracts in the McBride area, we were visited by a different black bear every day for 39

consecutive days. We think that we were working on a wildlife trail between the valley and the alpine pastures. The dogs chased all of them away without incident. The shepherds had developed such confidence in their dog pack that they saw the bear visits (and subsequent dog explosions) as a pleasant interruption in an otherwise fairly boring day.

On another cut block in the Stewart area, we were visited by 8 individual grizzly bears in a one week period. This was not fun. We did not want to be there, but the client threatened us with contract termination if we refused to do that block. Meanwhile, in downtown Hyder (only 100 km from our work site) a grizzly killed and partially ate a man behind the pub. The bears on our block did not really do anything wrong, it’s just that it was quite stressful that they were grizzly bears, that they were so big and that they were there on our worksite.

Two of them in particular were unusually huge. I was totally unprepared for the size of them, despite the numerous bear movies and documentaries I had seen, plus all of the previous bear experiences of my more than 30 years of bush work. They were much bigger than I had ever realized that they could possibly get. They looked and behaved like two big bulls.

We were at camp and all of our dogs were with the sheep flock when these two giants started casually walking towards us. Obviously those two grizzlies knew that they were the kings of the forest. They clearly were not afraid of us whatsoever. We felt completely naked, and fairly stupid. I realized that our travel trailers were basically cardboard boxes, that my .303 rifle was a toy, and that I don’t shoot well anyway. It was terrifying. We were about to jump into the truck and race away when those two monsters simply changed directions and casually wandered away when they felt like it. Nothing had really happened—except that I got another reminder of the vulnerability of all silvicultural workers, and of my own mortality. I am now much more serious about bears and the danger they represent to us.

In conclusion, I will repeat that I believe that bear dogs should become a normal, everyday BC silvicultural tool. If you think that buying and caring for dogs is too much trouble, I suggest you just look at it as though the next silvicultural worker to be killed may be you—and then decide whether getting a few dogs is worth the extra effort or not.

The Club once again thanks Mr. Dennis Loxton, the Western Silvicultural Contractors' Association and BC Forest Safety Council for granting express permission to reproduce this article for the benefit of visitors to our site.

The article provides great insight into the lives of Great Pyrs as livestock guardian dogs.

Here is the story of a family pet that defended its family against a Bear attack.

Let's leave our livestock guardian dogs and go home.

Breaking News

-

Courtesy - Bear

Apr 09, 25 09:09 AM

Bear DOB: October 2018 Location: Midland, Ontario Pyr/Maremma? mix Single family home with a large securely-fenced property or a hobby farm. Purchased/adopted -

Courtesy Post - Willow

Apr 09, 25 09:07 AM

DOB: March 26th, 2022 Location: London Ontario Cross Pyr/Collie Obtained her privately through a friend. How long have you had her? 10 months Spayed -

Lucy

Apr 09, 25 09:06 AM

*Foster-to-Adopt* or *Foster* DOB: January 3, 2024 Location: Acton, Ontario She will need a single-family home with a securely fenced yard of at least -

Remi

Apr 09, 25 07:44 AM

Location: Acton, Ontario DOB: February 2024 This sweet white fluffy Remi has a sad story. Remi, while his family was in the midst of moving, escaped and -

Grieving Dog

Apr 04, 25 06:17 PM

Background: I am seeking some feedback if anyone has had experience with bonded pairs. Thank you! We have been fortunate to love 2 x almost 10 year -

Leo

Mar 12, 25 06:32 AM

*ADOPTED* DOB: September 2023 (almost 1.5-years-old) Location: Acton, ON Single family home with a securely fenced yard required. This sweetheart was -

Buster

Mar 10, 25 03:36 PM

*Buster is going back to his original family as things have brightened up in their lives and he'll have a wonderful life on acreage.* Buster had to come -

Courtesy - Maya

Jan 08, 25 05:35 PM

*ADOPTED* Location: Dunnville, ON DOB: Jan. 3, 2021 (3.5 years) Spayed Companion Dog, Pyr mix Good with children. Single family home. Raw diet (species-appropriate)